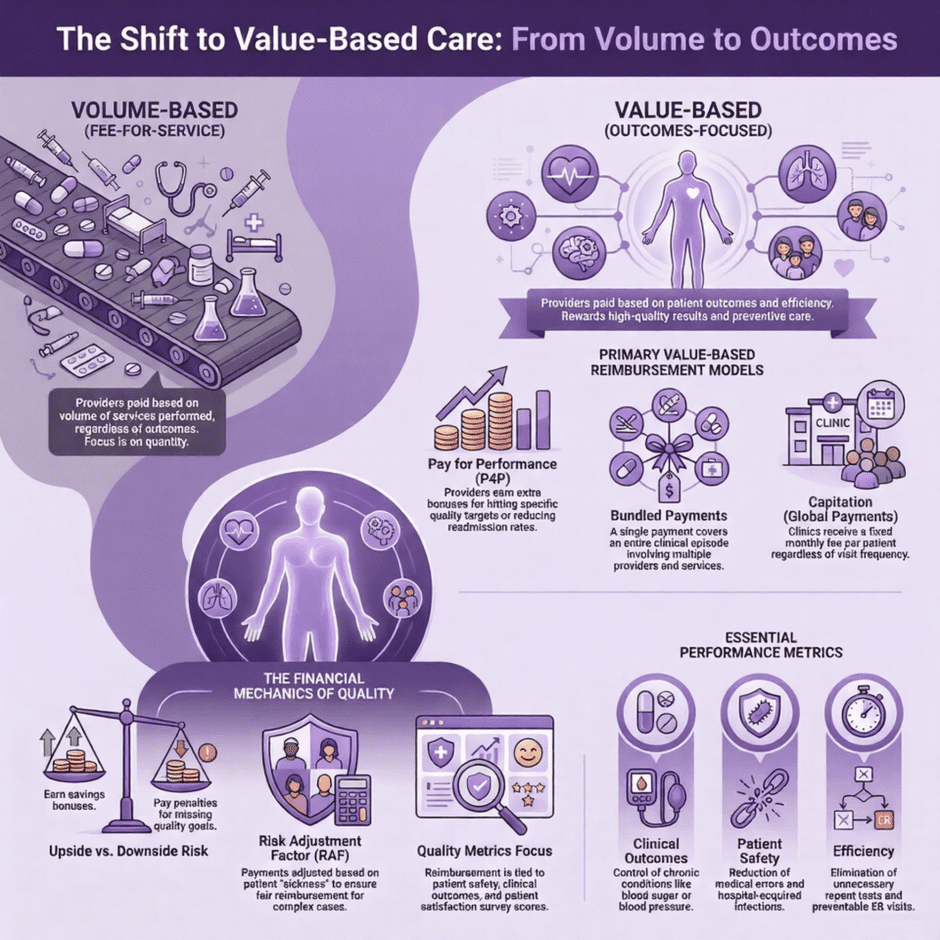

The way providers get paid is shifting from how many tasks they perform to how well those tasks actually help patients. For decades, the primary method was Fee-for-Service (FFS). In that old model, a clinic or hospital received a check for every blood draw, every X-ray, and every office visit. While that sounds straightforward, it often led to a focus on volume rather than the actual health of the person sitting in the exam chair.

Value-based care (VBC) turns that idea on its head. Instead of rewarding a high number of visits, it rewards a high quality of results. It asks a simple question.

Did the patient get better, and did we provide that care at a reasonable price?

For clinics and hospitals, this means the money coming in is now tied to performance metrics and patient outcomes.

The Foundation of Value-Based Reimbursement

To visualize how this works, think of it as a shift from a “pay-per-item” menu to a “subscription for health.” In a clinic, if a provider spends an hour talking a patient through a lifestyle change that prevents a heart attack, the FFS model might only pay for a standard office visit. In a value-based model, that provider might receive a bonus because that patient avoided a costly hospital stay.

To visualize how this works, think of it as a shift from a “pay-per-item” menu to a “subscription for health.” In a clinic, if a provider spends an hour talking a patient through a lifestyle change that prevents a heart attack, the FFS model might only pay for a standard office visit. In a value-based model, that provider might receive a bonus because that patient avoided a costly hospital stay.

This system relies on data. Payers, like Medicare or private insurance companies, look at specific metrics to decide how much to pay.

These metrics often include:

- Patient Safety: Are there low rates of infections or medical errors?

- Clinical Outcomes: Is the diabetic patient’s blood sugar under control?

- Patient Experience: Did the patient feel heard and cared for?

- Efficiency: Were unnecessary repeat tests avoided?

Common Models for Clinics and Hospitals

Not every value-based agreement looks the same. Depending on the size of the facility and the goals of the payer, the reimbursement might follow one of several paths.

1. Pay for Performance (P4P)

This is often the first step away from traditional billing. The clinic still gets paid for services, but they receive extra bonuses if they hit certain quality targets. If a hospital reduces its readmission rates for pneumonia patients below a certain threshold, the payer adds a percentage to their total reimbursement. Conversely, if they miss those targets, they might see a small reduction in pay.

2. Bundled Payments (Episode-Based Care)

Instead of paying the surgeon, the hospital, and the physical therapist separately for a knee replacement, the payer sends one single payment for the entire “episode.” The team must work together to manage the patient’s recovery within that budget. If they do it efficiently and the patient recovers well, they keep the extra money. If there are preventable errors that require more surgery, the providers often have to cover those costs themselves.

3. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs)

An ACO is a group of doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers who come together to provide coordinated care to a specific group of patients. They share the financial risk and the rewards. If the ACO manages to lower the total cost of care for their patients while maintaining high quality, the payer shares those savings with the providers. This encourages the clinic to call the patient after a visit to make sure they filled their prescription, preventing a future emergency room trip.

4. Capitation (Global Payments)

This is the most direct departure from the old way. In a capitated model, a clinic or hospital receives a set amount of money per patient per month, regardless of how many times that patient comes in. If the patient stays healthy and rarely needs the doctor, the clinic keeps the fee. If the patient becomes very ill, the clinic uses that money to provide the necessary care. This makes the provider highly invested in preventive medicine.

The Financial Mechanics of Quality

For a hospital or clinic to receive these payments, they have to prove their worth through rigorous reporting. It is no longer enough to just send a claim with a CPT code. Facilities must now track and report on hundreds of data points. When a clinic enters a value-based contract, they usually work with a benchmark. This benchmark is a “target price” for care based on historical data. If the clinic spends less than the benchmark while meeting quality goals, they “earn” the difference. This is called “upside risk.” Some contracts also include “downside risk,” where the clinic has to pay money back if they spend too much or if their quality scores are too low.

For a hospital or clinic to receive these payments, they have to prove their worth through rigorous reporting. It is no longer enough to just send a claim with a CPT code. Facilities must now track and report on hundreds of data points. When a clinic enters a value-based contract, they usually work with a benchmark. This benchmark is a “target price” for care based on historical data. If the clinic spends less than the benchmark while meeting quality goals, they “earn” the difference. This is called “upside risk.” Some contracts also include “downside risk,” where the clinic has to pay money back if they spend too much or if their quality scores are too low.

Risk adjustment is another major piece of this puzzle. Not every patient is the same. A 25-year-old athlete costs less to care for than an 80-year-old with three chronic conditions. To make reimbursements fair, payers use risk adjustment. This involves looking at the patient’s diagnosis codes to determine how “sick” they are. A clinic with a higher “Risk Adjustment Factor” (RAF) score will receive higher base payments because the payer recognizes that their patients require more resources and time.

Why Hospitals Face Different Hurdles

Hospitals have a different set of obstacles compared to small clinics. Because a hospital deals with high-acuity care (like surgeries, emergency rooms, and intensive care) the financial stakes are much higher. A single “never event,” such as a patient falling or getting a hospital-acquired infection, can lead to massive financial penalties under value-based care.

For a hospital, value-based reimbursement often centers on the “Value-Based Purchasing” (VBP) program used by Medicare.

This program scores hospitals on several domains:

- Safety: Avoiding things like catheter-associated urinary tract infections.

- Clinical Outcomes: Mortality rates for heart failure or hip surgeries.

- Person and Community Engagement: Survey results from patients regarding the communication of nurses and doctors.

- Efficiency and Cost Reduction: The total cost of care for a Medicare patient during their stay and the 30 days following discharge.

If a hospital excels in these areas, Medicare increases their base operating DRG (Diagnosis-Related Group) payments. If they fail, their payments are trimmed. This makes the hospital a partner in the patient’s long-term health, rather than just a place to fix an immediate crisis.

The Daily Impact on Clinic Operations

Moving to this model isn’t just a change for the accounting department; it changes how the front desk and the clinicians work every day. In the old world, the goal was to get the patient in and out quickly. In a value-based world, the goal is to ensure the patient doesn’t need to come back for the same issue next week.

Moving to this model isn’t just a change for the accounting department; it changes how the front desk and the clinicians work every day. In the old world, the goal was to get the patient in and out quickly. In a value-based world, the goal is to ensure the patient doesn’t need to come back for the same issue next week.

Clinics often find they need more staff, but not necessarily more doctors. They hire “care managers” or “patient navigators” whose entire job is to follow up with patients between appointments. These staff members check if a patient filled their prescription, help them find transportation to a specialist, or teach them how to use a home blood pressure cuff. While this adds overhead cost to the clinic, the goal is that these actions lead to better outcomes, which triggers the bonuses that pay for the staff.

Documentation also becomes a massive priority. If a doctor forgets to document a chronic condition, like chronic kidney disease, the patient looks “healthier” on paper than they actually are. This lowers the risk score, which in turn lowers the payment the clinic receives to care for that patient. Precise coding becomes the lifeblood of the clinic’s revenue stream.

Data: The New Currency

To participate in these payment models, clinics and hospitals need robust technology. They must be able to pull reports on their entire patient population at once.

They need to know:

- Which patients have missed their annual wellness visits?

- Which patients have high blood pressure that isn’t under control?

- Which patients were recently seen in an emergency room?

Without this data, a clinic is flying blind. They might think they are providing great care, but if they cannot prove it with numbers, the payers will not issue the incentive checks. This shift requires a level of data management that many smaller clinics find daunting.

Challenges and Opportunities

While the goal of value-based care is noble, the path is not always easy. One of the biggest hurdles is the “transition period.” During this time, a clinic might have 70% of its patients on traditional Fee-for-Service and 30% on value-based contracts. This forces the staff to follow two different sets of rules. They have to maximize volume for some patients while minimizing it for others to achieve savings. This creates a friction that requires careful management.

Another challenge is the social determinants of health. A clinic can give a patient the best insulin in the world, but if that patient lives in a “food desert” and cannot buy healthy food, or if they are homeless and have no place to store the medicine, their outcomes will stay poor. Many value-based models are beginning to incorporate “social risk” into their payments, giving providers more money to help address these non-medical needs.

Despite these hurdles, the opportunity for providers is significant. When a clinic or hospital becomes more efficient, they often find that they are less rushed. They spend more time on meaningful interactions and less time on the “hamster wheel” of high-volume billing. This can lead to lower burnout for doctors and nurses, as they feel they are actually making a difference in the long-term health of their neighbors.

The Role of Payer Contracting

Success in this environment often starts long before a patient walks through the door. It starts during the negotiation of the payer contract. A clinic must ensure that the “quality targets” set by the insurance company are realistic for their specific patient population. If a payer sets a goal for weight loss that is impossible to meet given the local demographics, the clinic is doomed to fail financially from the start.

Success in this environment often starts long before a patient walks through the door. It starts during the negotiation of the payer contract. A clinic must ensure that the “quality targets” set by the insurance company are realistic for their specific patient population. If a payer sets a goal for weight loss that is impossible to meet given the local demographics, the clinic is doomed to fail financially from the start.

This is where having expert help in the background becomes vital. Negotiating these contracts requires an eye for detail and a deep knowledge of how different payers value specific codes and outcomes. It also requires the ability to look at historical billing data to predict how a new value-based model will affect the bottom line.

A Detailed Look at Incentive Structures

Let’s look closer at how a clinic might actually see a check arrive. Imagine a small primary care group with 1,000 Medicare patients. Under a “Shared Savings” model, the payer calculates that based on the health of those patients, it should cost about $10 million a year to care for them.

If the clinic uses care managers to keep those patients out of the ER and manages their chronic illnesses so well that the total cost for the year is only $9 million, there is $1 million in “savings.” The payer might keep $500,000 and give the clinic the other $500,000 as a bonus. This is on top of the money the clinic already earned for office visits.

However, if the clinic spent $11 million because they didn’t manage the patients well, they might have to pay a penalty. This “skin in the game” is what drives the change in behavior. It forces every person in the building to think about the long-term cost and quality of every decision.

The List of Key Metrics

Most value-based models focus on a core set of data points that help determine these payouts.

These usually include:

- HEDIS Scores: A set of standardized performance measures related to things like immunizations and cancer screenings.

- CAHPS Surveys: National surveys that measure how patients perceive their care experience.

- Readmission Rates: The percentage of patients who end up back in the hospital within 30 days of leaving.

- Average Cost Per Member: The total spend on a patient over a year compared to the average for that region.

- Preventable Emergency Department Visits: Visits for things like ear infections or minor rashes that could have been handled in a clinic setting.

The Future Terrain

The goal of the industry is to move more providers into “two-sided risk.” This is where the provider takes on both the chance for a bonus and the threat of a penalty. While this sounds scary, it offers the highest potential for revenue. For a hospital, it allows them to act as their own mini-insurance company, managing the health of their community and reaping the financial rewards when that community stays well.

The goal of the industry is to move more providers into “two-sided risk.” This is where the provider takes on both the chance for a bonus and the threat of a penalty. While this sounds scary, it offers the highest potential for revenue. For a hospital, it allows them to act as their own mini-insurance company, managing the health of their community and reaping the financial rewards when that community stays well.

The technology used to track these metrics is also getting better. We are seeing more tools that flag high-risk patients in real-time. If a patient with heart failure misses an appointment, the system automatically alerts the clinic to call them. This level of proactive care is the hallmark of the value-based movement.

For generations, the American medical system has been a “sick care” system. You got sick, you went to the doctor, and the doctor got paid. If you stayed healthy, the doctor made nothing. Value-based reimbursement flips this. It turns the doctor into a partner in your health.

This creates a more sustainable model for the country. As the population ages, we cannot afford to just keep paying for more and more procedures. We have to pay for what works. This shift helps clinics and hospitals stay financially viable while actually improving the lives of the people they serve.

Summary and Support

The transition toward value-based care is a fundamental shift in the business of medicine. It moves the focus toward efficiency and longevity, ensuring that the financial health of a hospital is directly tied to the physical health of its community. While the data requirements are high, the potential for better patient lives and more stable revenue streams is a significant draw for modern practices.

The transition toward value-based care is a fundamental shift in the business of medicine. It moves the focus toward efficiency and longevity, ensuring that the financial health of a hospital is directly tied to the physical health of its community. While the data requirements are high, the potential for better patient lives and more stable revenue streams is a significant draw for modern practices.

Navigating the details of these models requires a team that knows the ins and outs of the system. At Medwave, we see the weight these changes place on your shoulders. We specialize in medical billing, credentialing, and payer contracting to ensure your facility stays current with these shifting models. We handle the paperwork, the negotiations, and the billing hurdles so that you can focus on the clinical work that truly drives these value-based results. By ensuring your contracts are fair and your billing is accurate, we help you secure the revenue you deserve.